L’article se penche sur la conception largement répandue des ‘borderscapes’ dans la recherche sur les frontières et présente les fondamentaux de l’approche. À cet effet, les utilisations de ce terme émergent et les conceptions qu’il implique sont tout d’abord développées. Sur cette base, les ‘borderscapes’ sont systématisés comme une formation relationnelle, diffusée, épisodique, en perspective et contestée, liée aux frontières nationales. En partant de ces constats, nous montrerons dans quelle mesure les ‘borderscapes’ rompent avec l’idée ‘traditionnelle’ de frontière en tant que binarité (territoriale) et portent un concept alternatif de frontière : La frontière est ici intégrée à un grand nombre de processus sociétaux modifiables et malléables, interconnectés entre eux de manière trans-scalaire et controversée et qui, dans leur interaction complexe, établissent ou (dé)stabilisent des frontières. L’approche de ‘borderscapes’ transforme donc les frontières en paysages de leurs efficacités et négociations multiples, qui peuvent avoir lieu aux ‘bords territoriaux’, mais qui ne doivent pas obligatoirement y être localisés. L’approche représente ainsi une proposition analytique qui échappe au « territorial trap » (litt. « piège territorial ») (Agnew, 1994), sensibilise à la complexité des frontières et considère ces-dernières également comme des ressources. Malgré les efforts déployés pour définir l’approche ‘borderscapes’ de manière plus précise, l’approche reste floue. Les fondamentaux exposés définissent plutôt un cadre théorique et conceptuel, dans lequel évoluent des chercheur.e.s sur les frontières sensibles à la complexité et qui laisse la place à des appropriations spécifiques. Celles-ci sont enfin présentées à l’aide d’exemples issus des études culturelles des frontières et nous discuterons le degré d’ouverture conceptuelle de l’approche, qui se manifeste particulièrement dans des ambiguïtés méthod(olog)iques.

The article examines the understanding of ‘borderscapes’ that is widespread in Border Studies, and lays out the basic features of the approach. To do so, the uses of the emerging term and its implied understandings will first be presented. On this basis, ‘borderscapes’ is systematized as a relational, diffused, episodic, perspectival, and contested formation that is related to national borders. The article will also show the extent to which ‘borderscapes’ breaks with the ‘traditional’ idea of border as a (territorial) binary and will strengthen an alternative concept of border: border is embedded here in a multitude of social processes that can be changed and shaped, relate to one another in a transscalar and contested manner, and, in their complex interplay, produce effects that establish or (de)stabilize national borders. ‘Borderscapes’ transfers borders into the landscapes of their multiple effects and negotiations, which certainly can take place on ‘territorial edges’, but do not necessarily have to be located there. The approach thus makes an analytical offer that escapes the “territorial trap” (Agnew, 1994), creates sensitivity for the complexity of borders and also regards them as resources. Despite efforts to outline ‘borderscapes’ more definitely, the approach cannot be clearly defined. Rather, the principles outlined lay out a theoretical-conceptual framework in which complexity-sensitive Border Studies researchers move and in which room for specific appropriations is left. These principles will then be presented using examples from cultural border studies, moreover the conceptual openness of the approach, which is particularly reflected in method(olog)ical ambiguities, will be discussed.

Der Beitrag arbeitet das in der Grenzforschung weit verbreitete Verständnis von ‚borderscapes‘ heraus und gibt den Ansatz in seinen Grundzügen wieder. Dazu werden zunächst die Verwendungen des aufkommenden Begriffs und die damit implizierten Verständnisse dargelegt. Darauf aufbauend wird ‚borderscapes’ als relationale, diffundierte, episodische, perspektivische und umkämpfte Formation systematisiert, die mit nationalen Grenzen in Beziehung steht. Darüber wird gezeigt, inwiefern ‚borderscapes‘ mit der ‚traditionellen‘ Idee von Grenze als (territoriale) Binarität bricht und einen alternativen Grenzbegriff stark macht: Grenze wird hier in eine Vielzahl gesellschaftlicher Prozesse eingelagert, die wandelbar und gestaltbar sind, sich transskalar und in umkämpfter Weise aufeinander beziehen und in ihrem komplexen Zusammenspiel Effekte der Einsetzung oder (De-)Stabilisierung von nationalen Grenzen hervorbringen. ‚Borderscapes‘ überführt Grenzen also in die Landschaften ihrer multiplen Wirksamkeiten und Aushandlungen, die durchaus an ‚territorialen Rändern‘ stattfinden können, aber nicht zwangsläufig dort verortet sein müssen. Damit macht der Ansatz ein analytisches Angebot, das der „territorial trap“ (Agnew, 1994) entkommt, für die Komplexität von Grenzen sensibilisiert und diese außerdem als Ressourcen betrachtet. Trotz der Bemühung ‚borderscapes‘ näher zu umreißen, kann der Ansatz nicht eindeutig bestimmt werden. Die dargelegten Grundzüge stecken vielmehr einen theoretisch-konzeptionellen Rahmen ab, in dem sich komplexitätssensible Grenzforscher*innen bewegen und der Spielräume für spezifische Aneignungen lässt. Solche werden abschließend anhand von Beispielen der kulturwissenschaftlichen Grenzforschung vorgestellt und die konzeptionelle Offenheit des Ansatzes, die sich besonders in method(olog)ischen Mehrdeutigkeiten widerspiegelt, besprochen.

Borderscapes

1. Introduction

Les ‘borderscapes’ en tant qu’approche, ce qui inclut des aspects conceptuels et méthodologiques, s’inscrivent dans la continuité du « bordering turn » (Cooper, 2020, p. 17), qui s’est produit au cours de la renaissance des frontières et des impulsions scientifiques des années 2010 qui l’ont accompagné. Malgré une définition confuse et une certaine ouverture conceptuelle, l’approche de ‘borderscapes’ est fréquente dans les études géopolitiques et culturelles des frontières, à tel point que l’on pourrait avoir l’impression que « speaking about borderscapes is almost a fashion » (dell’Agnese et Amilhat-Szary, 2015, p. 5). Cela sous-entend déjà que l’approche est largement répandue. Les débats ou les réflexions critiques concernant son opérationnalisation restent cependant une exception. Outre ces critiques, il faut souligner un certain nombre de points forts de cette approche, qui ont largement imposé une conception différenciée des frontières dans la recherche sur les frontières. La conception des frontières dans les ‘borderscapes’, qui est implicite pour des raisons didactiques, rejoint le « complexity shift » (Wille, 2021) en tant que tendance encore récente dans la recherche sur les frontières. Cela inclut les préoccupations des chercheurs sur les frontières, de ne plus considérer les frontières « uniquement » comme les effets de processus de frontiérisation « gérable » (Van Houtum/Van Naerssen, 2002) ou comme des « lines in the sand » incontestées (Parker/Vaughan-Williams 2009), mais bien plus d’examiner les frontières en tant qu’ensembles puissants d’acteurs multiples, de scènes sociales, d’(im)matérialités, de multilocalités, de multivalences ou de temporalités. Cette perspective plus complexe, qui conçoit la frontière comme une formation efficace (et non pas existante en dehors d’une telle formation) et qui s’intéresse à ce mode de fonctionnement, implique également l’approche des ‘borderscapes’. Elle compare les frontières avec des formations trans-scalaires d’éléments, dont l’interaction complexe fait émerger des frontières : « The borderscape is not purely an external effect of the border, but an assemblage in which bordering takes place. » (Schimanski, 2015, p. 40)

L’idée de la formation qui représente ici la frontière est exprimée dans les nombreuses reformulations, qui tentent d’expliquer les ‘borderscapes’ : « panoramas », « contexts » (Scott, 2020a, p. 151), « zone » (Rajaram et Grundy-Warr, 2007, p. xxx), « spaces » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 18), « fluid field » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 26), « sites of struggle » (Brambilla et Jones, 2019) ou « horizon » (Stojanovic, 2018, p. 147). Les reformulations vont des conceptions statiques aux conceptions dynamiques, mais aussi des conceptions abstraites aux conceptions concrètes et sont pour la plupart liées à l’espace. L’éventail d’interprétations fait référence aux différentes interprétations de l’approche dans la recherche sur les frontières, qui, elle-même, est considérée comme un « interdisciplinary borderland » (Cooper, 2020, p. 18). Cet article se rend dans ce ‘borderland’ pour reconstruire les fondamentaux de l’approche, à la lumière de son « irresistible vagueness » (Krichker, 2019, p. 2) et de sa « polysemicity » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 20). À cet effet, nous examinons d’abord les utilisations de ‘borderscapes’ à partir du passage au nouveau millénaire et les conceptions de ce terme qu’elles impliquent. La conception particulièrement répandue de ‘borderscapes’ est ensuite représentée par la « frontière en tant que paysage » et liée à ‘borderscapes’ en tant qu’approche de la recherche sur les frontières axée sur la complexité. À cette fin, les ‘borderscapes’ sont systématisés, principalement à l’aide des travaux de l’anthropologue Chiara Brambilla, en tant que formation relationnelle, diffusée, épisodique, en perspective et contestée, liée à une ou plusieurs frontières nationales. Enfin, nous présenterons les appropriations possibles de l’approche à l’aide d’exemples issus des études culturelles des frontières, et discuterons l’ouverture conceptuelle de ‘borderscapes’, qui se manifeste particulièrement dans des ambiguïtés méthod(olog)iques.

2. Utilisations du terme

Le terme ‘borderscapes’ a été façonné par les artistes Guillermo Gómez-Peña et Roberto Sifuentes, lorsqu’ils ont présenté la performance Borderscape 2000: Kitsch, Violence, and Shamanism at the End of the Century (1999) il y a vingt ans au Magic Theater (San Francisco) (dell’Agnese et Amilhat Szary, 2005, p. 4 et suiv.). Après le passage au nouveau millénaire, le terme est aussi présent dans le débat scientifique, bien que tout d’abord de manière sporadique : dans l’essai Borderscapes, the Influence of National Borders on European Spatial Planning d’Arjan Harbers (2003), dans le chapitre Boundaries in the Landscape and in the City de Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper et Marieke Kuipers (2004), dans l’exposé Bollywood’s Borderscapes d’Elena dell’Agnese (2005) lors d’une conférence de l’American Association of Geographers ou enfin dans le livre Stories of the ‘Boring Border‘: The Dutch-German Borderscape in People’s Minds d’Anke Strüver (2005).

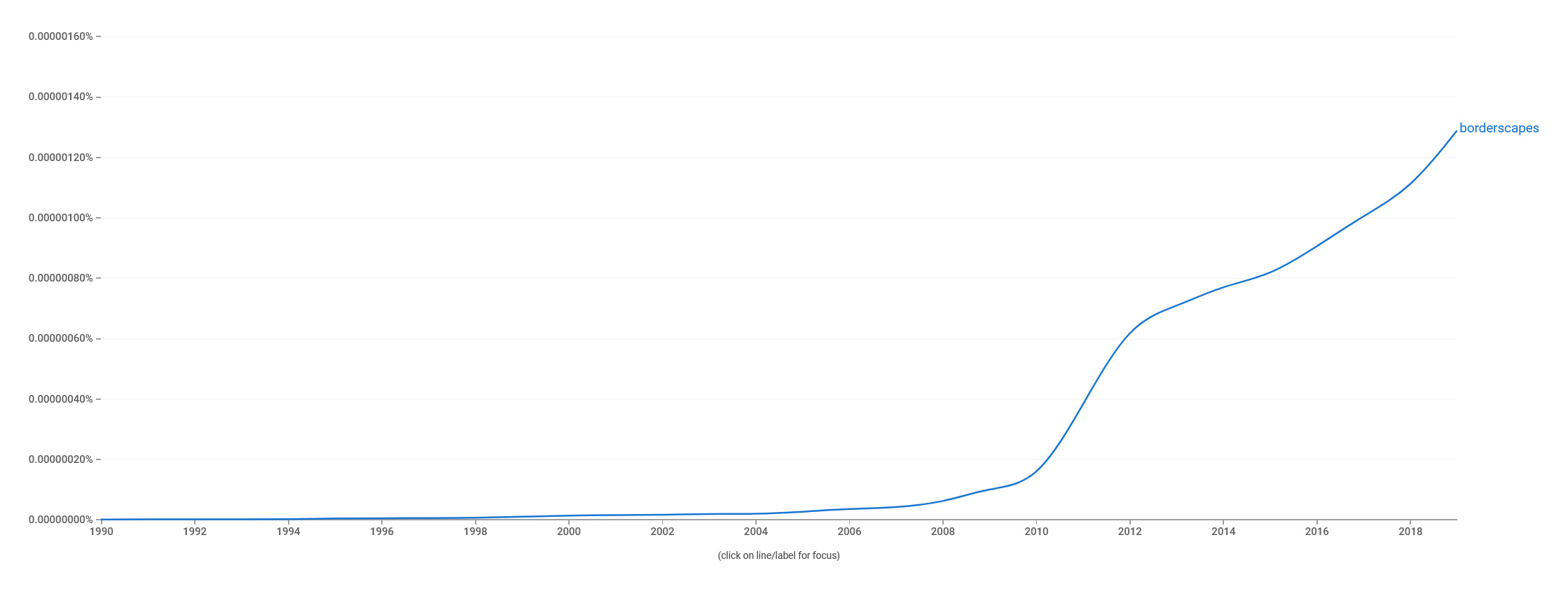

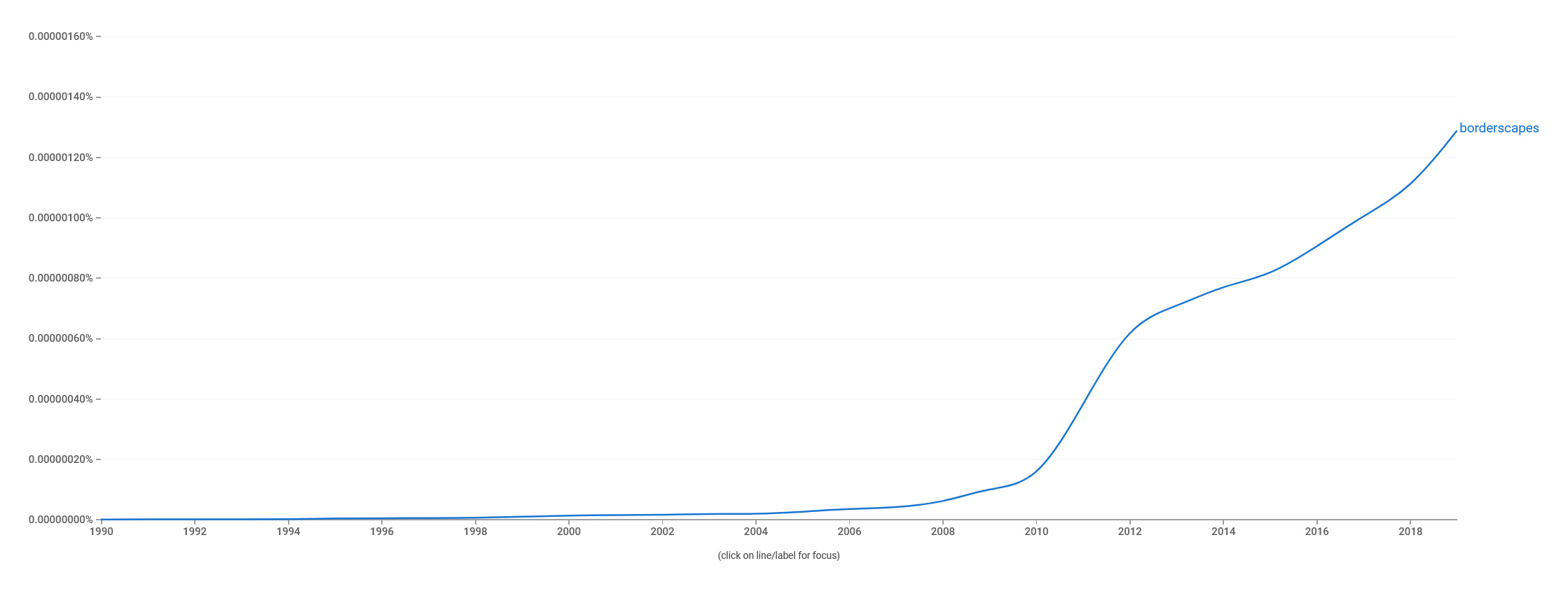

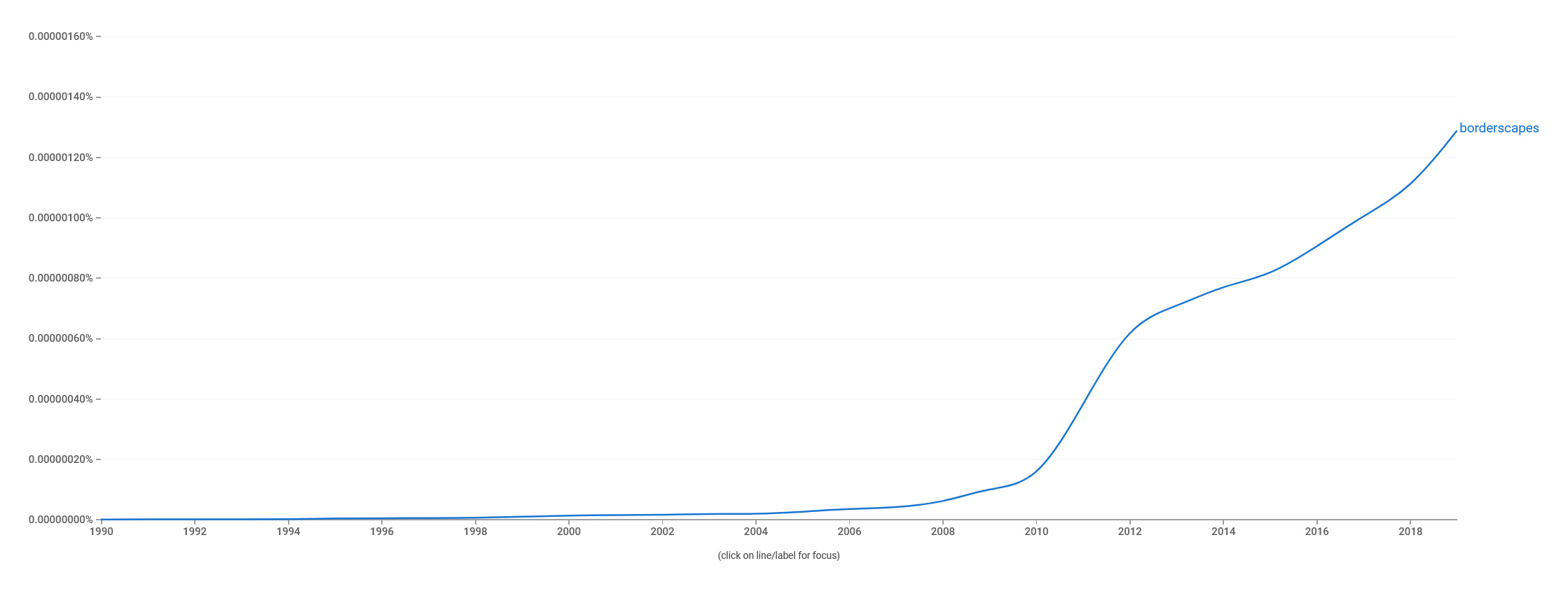

Après le milieu des années 2000, le terme ‘borderscapes’ est de plus en plus répandu dans le débat scientifique. La publication du livre Borderscapes: Hidden Geographies and Politics at Territory’s Edge par le socio-anthropologue Prem Kumar Rajaram et le géographe Carl Grundy-Warr (2007), ainsi qu’une série de conférences dans le cadre de l’International Geographical Union y ont fortement contribué : « Borderscapes : Spaces in Conflicts/Symbolic Places/Networks of Peace » (Trento, 2006), « Borderscapes II : Another Brick in the Wall ? » (Trapani, 2009) et « Borderscapes III » (Trieste, 2012). Dans les années 2010, le terme commence à gagner en popularité, probablement à la suite du projet de recherche « EUBORDERSCAPES – Bordering, Political Landscapes and Social Arenas: Potentials and Challenges of Evolving Border Concepts in a post-Cold War World » (Euborderscapes, 2016). Le projet multidisciplinaire (2012-2016) avec 22 partenaires venant de 17 pays, financé par le 7e programme-cadre de recherche européen, a généré un grand nombre d’impulsions intellectuelles et de publications scientifiques qui ont profilé le terme comme une approche de la recherche sur les frontières axée sur la complexité. Le recueil Borderscaping: Imaginations and Practices of Border Making (Brambilla et Laine et al., 2015), parmi d’autres, en fait partie.

L’aperçu du mot composé de « border » et « landscapes » reflète son utilisation prédominante au pluriel, sa popularité relativement récente et son utilisation dans différents domaines scientifiques. Plusieurs conceptions du terme, qui apparaissent de manière plus ou moins réfléchies sur le plan théorique et conceptuel dans la recherche sur les frontières, y sont aussi associées (ci-dessous également dell’Agnese et Amilhat Szary, 2005) :

(1) Paysage à la frontière : L’essai de Harber (2003) est exemplaire pour comprendre les ‘borderscapes’ en tant que paysage à la frontière. Il conçoit les ‘borderscapes’ comme un paysage caractérisé ou influencé par la présence d’une frontière nationale : « [W]e shall describe the distortions borders bring to the built environment or nature as ‘border solidifications’, or borderscapes. » (Harbers, 2003, p. 143) Par conséquent, les ‘borderscapes’ désignent un espace physique situé sur ou le long d’une frontière nationale, dans lequel les discontinuités de la souveraineté nationale se matérialisent. Cette conception s’inscrit également dans le prolongement de certains travaux de géographie politique qui ont déjà thématisé le rôle de l’État en tant que « paysagiste » dans la première moitié du XXe siècle.

(2) Paysage à travers la frontière : Pour cette conception des ‘borderscapes’, il s’agit également de l’aménagement d’un espace physique en rapport avec des frontières nationales. Cependant, les auteures Dolff-Bonekämper et Kuipers (2004) ne demandent pas dans quelle mesure les discontinuités de la souveraineté nationale se matérialisent dans un paysage à la frontière, mais elles s’interrogent du rôle de la frontière dans le processus de l’aménagement d’un paysage. À cet effet, elles évoquent avec Julian Minghi et Dennis Rumley (1991) le développement territorial dans les régions frontalières et les discontinuités efficaces dans ce processus : compétences, style politique, processus décisionnels, etc. Les auteurs conçoivent donc les ‘borderscapes’ comme un paysage transfrontalier, qui apparaît par le biais de la frontière, c’est-à-dire à travers des négociations productives des discontinuités impliquées par la frontière nationale.

(3) La frontière en tant que paysage : Cette conception conçoit la frontière elle-même comme un paysage en constant changement et s’appuie, tout comme l’artiste de performance Guillermo Gómez-Peña (Kun, 2000), sur les « Scapes of Globalization » d’Arjun Appadurai (1996). Dans le cadre des débats des années 1990 sur la mondialisation, l’anthropologue utilise ce concept pour décrire le monde comme une formation transnationale de flux, de processus d’échanges et de chevauchements, qui représente un paysage mondial hybride et instable, contrairement à l’idée d’un monde organisé de manière statique et binaire. Le terme paysage est ici employé de manière métaphorique, pour décrire des interdépendances dynamiques et trans-scalaires qui peuvent être représentées de manière spatiale, mais pas dans la mosaïque de l’ordre national. Dans ce sens, les ‘borderscapes’, s’émancipent de l’espace sur ou le long de la « bord territoriale » et représentent eux-mêmes un espace mobile et relationnel :

In line with Appadurai’s reflection, the borderscapes concept brings the vitality of borders to our attention, revealing that the border is by no means a static line, but a mobile and relational space. […] Thus, the concept of borderscape enables a productive understanding of the processual, de-territorialised and dispersed nature of borders and their ensuing regimes and ensembles of practices. (Brambilla, 2015, p. 22)

Les conceptions des ‘borderscapes’ présentées ici s’appuient toutes sur un paysage, cependant avec différentes orientations. Ainsi, les deux premières notions se concentrent-elles sur un espace physique et territorial en tant que paysage, dont la position géographique sur, le long ou au-delà d’une frontière nationale est centrale et qui est aménagé par une instance externe, à chaque fois de manière différente. Pour la troisième conception du terme, l’idée du paysage terrestre-spatial est remplacée par celle d’un contexte d’interdépendance, dont l’aménagement n’émane d’aucune instance externe et dont la localisation géographique est moins importante. Le paysage, conçu ici comme multilocal, représente la frontière, à laquelle est attribuée une certaine force créatrice en tant que formation dynamique qui lui est propre. En conséquence, la signification performative de « landscape », qui vise une transformation ou un aménagement (shape) socioculturel, revêt une accentuation spécifique et parfois critique dans la conception de « frontière en tant que paysage » : « the notion of ‘scapes’ is part of a political project of ‘making’ that highlights the ways in which the borderscape affords particular sets of reproductive practices and shapes political subjectivities in a particular manner. » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 24) Les ‘borderscapes’ au sens de « frontière en tant paysage » divergent donc à plusieurs égards, des conceptions précédentes. Parallèlement, la « frontière en tant que paysage » est considérée comme la conception de ‘borderscapes’ la plus répandue dans la recherche actuelle sur les frontières (Krichker, 2019, p. 4), c’est pourquoi elle continue d’être approfondie.

3. Frontière comme paysage

La popularité de l’approche des ‘borderscapes’ relève sans doute du projet de recherche mentionné ci-dessus, qui porte un nom similaire. L’une des chercheuses et chercheurs sur les frontières participant, a fortement contribué à ce que les ‘borderscapes’ puissent évoluer à partir d’un terme émergent en une approche largement reçu au sein de la recherche sur les frontières axée sur la complexité : l’essai de Chiara Brambilla Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscape Concept (2015) ne propose certes pas de définition ou opérationnalisation exhaustive de l’approche, mais offre un grand nombre de perspectives théoriques et de réflexions conceptuelles, sur la façon dont les frontières peuvent être pensées et enfin examinées de manière complexe et critique. Dans l’essai, l’anthropologue veut présenter « a novel ontological outlook for the contemporary situation of globalisation and transnational flows where borders appear, disappear, and reappear with the same but different locations, forms and functions. » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 26) À cet effet, elle s’inscrit dans la continuité du courant encore récent à l’époque des Critical Border Studies (Parker/Vaughan-Williams et al. 2009 ; Parker/Vaughan-Williams 2012). Elle tente, par le biais d’approches alternatives qui sortent du modèle de pensée occidentale des binarités fixes et des frontières en tant que constructions instables dans l’espace et le temps, de se pencher sur des thèmes et des aspects que la recherche sur les frontières n’avait jusqu’alors presque pas abordés. Brambilla propose à cette fin une « processual ontology » (Brambilla 2015, p. 26) pour les frontières, qui reconnaît « that reality is evolving and constantly emerges and reemerges showing that being and becoming are not inseparable. » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 26)

Selon cette perspective, qui souligne le caractère factice social et le caractère non-figé des frontières, les pratiques de frontiérisation sont conçues comme des performances perpétuellement reproduites et dynamiques, intégrées dans des processus sociétaux ou qui s’expriment à travers ceux-ci. La focalisation sur les arènes sociétales des frontières est due à l’intérêt « to ‚humanise‘ borders » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 27), par lequel Brambilla souhaite obtenir un regard sur les représentations collectives, les expériences individuelles ou les efficacités des frontières et les rendre analysables : « […] focusing on how borders are embedded in the practice of the ordinary life and continuously emergent through the performative making and remaking of difference in everyday life. » (Brambilla, 2021a, p. 15). En outre, il s’agit d’un point de vue critique sur les frontières, qui se concentre sur la négociation dans la vie quotidienne de pratiques de frontiérisation éthiquement ou légalement légitimées d’une part et des pratiques de frontiérisation guidées par la résistance ou la subversion d’autre part (Brambilla, 2015, p. 20). Brambilla ne conçoit pas de tels processus de négociation au croisement des « hegemonic borderscapes » et des « counter-hegemonic borderscapes » uniquement comme des arènes sociétales, dans lesquelles des frontières s’articulent de manière particulièrement explicite. De tels « sites of struggle » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 29) mettent également en évidence des existences opprimées et des discours alternatifs, que l’approche souhaite rendre visibles. Dans ce contexte, Brambilla (2021a, p. 14) conçoit les ‘borderscapes’ « as shifting fields of claims, counter-claims and negotiations among various actors and historically contingent interests and processes. »

Avec ces explications, les fondamentaux des ‘borderscapes’ sont déjà exposés. Toutefois, la conception de « frontière comme paysage » soulève des questions supplémentaires, comme par exemple celle des composantes des ‘borderscapes’, de leurs liens, leurs références spatio-territoriales, et bien plus encore. Ces aspects de l’approche et d’autres sont, entre autres, abordés ci-après.

(1) Frontière comme formation relationnelle : En ce qui concerne les éléments qui composent les ‘borderscapes’, il n’existe aucun argument suffisant ou cohérent. Bien qu’il existe un consensus sur le fait que des éléments matériels et immatériels jouent un rôle pour les ‘borderscapes’, les caractéristiques qui les qualifient comme éléments des ‘borderscapes’ restent cependant indéterminées. Ainsi les affirmations sur les composantes des ‘borderscapes’, vont-elles de « all aspects of the bordering process » (Nyman et Schimanski, 2021, p. 5) jusqu’aux concrétisations d’un niveau d’abstraction très différent, en passant par « a broad range of the social processes around the borders » (Krichker, 2019, p. 5) ou « the various elements of bordering » (Bürkner, 2017, p. 86). Elles incluent les réglementations en matière de visa et d’entrée, les lois, la rhétorique politique, la littérature, l’art, les fonctionnaires, les connaissances, les institutions, les artefacts physiques, les discours, la surveillance, les barrières, les pratiques socioculturelles quotidiennes, etc. (Nyman et Schimanski, 2021 ; Bürkner, 2017 ; Laine, 2017 ; Brambilla, 2015). Quant à la question de savoir quels éléments constituent les « frontière comme paysage » semblent être une question à laquelle il faut répondre de manière empirique. Cette question peut être examinée pour savoir dans quelle mesure les éléments (im)matériels sont (rendus) empiriquement pertinents dans et à travers les ‘borderscapes’. En ce faisant, les relations (souvent en partie identifiées de manière inductive, en partie déterminées de manière déductive) semblent importantes, car elles indiquent qui ou quoi semble être pertinent dans les ‘borderscapes’ et fait ainsi partie de la formation.

Cependant, le rôle et les caractéristiques de cet établissement de liens restent également sous-déterminés, lorsque l’on se réfère uniquement de manière générale, sur le fait que les « borderscapes sont « a space [of] complex interactions » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 24), « a […] space connecting up all aspects of the bordering process » (Nyman et Schimanski, 2021, p. 5) ou une sorte de « meeting point of the various elements of bordering » (Bürkner, 2017, p. 86).

Des déterminations plus précises concernant les relations entre les composantes des ‘borderscapes’, peuvent être trouvées chez Scott (2017, p. 16) ou Laine (2017, p. 14), qui identifient une relation inclusive ou complémentaire, lorsque la « frontière comme paysage » associe à la fois des visions et des processus politiques, ainsi que des pratiques quotidiennes et des représentations. Rajaram/Grundy-Warr (2007, p. xxvi) spécifient davantage les relations, en considérant les tensions et les conflits comme un moment caractérisant les ‘borderscapes’ : « The borderscape is recognizable not in a physical location but tangentially in struggles. »

(2) Frontière comme formation diffusée : La question de la localisation des ‘borderscapes’ et de ses références spacio-territoriales apparaît dans le caractère factice social et dans la multiplicité. À cet effet, l’idée des arènes sociales, dans lesquelles des frontières apparaissent, est reprise : « the border becomes […] something camouflaged in a language and performance of culture, class, gender, and race […]. Such camouflage reproduces the border in the multiple localities and spatialities of state and society » (Rajaram et Grundy-Warr, 2007, p. x). Les arènes sociétales mentionnées, mais aussi beaucoup d’autres, représentent les processus sociaux multiples et dispersés dans l’espace, qui portent la signature des frontières. Les ‘borderscapes’ ou la formation de leurs arènes peuvent tout à fait « apparaître » à la ou le long d’une frontière nationale, mais leur localisation est principalement cernée par les efficacités ou les articulations sociales des frontières nationales, qui échappent cependant aux ordres nationaux. C’est à quoi renvoie également Schimanski (2015, p. 36), qui attribue aux ‘borderscapes’ « an inherent resistance to state demarcation » et mentionne des catégories d’ordres alternatives pour la localisation de la « frontière en tant que paysage » : « [T]he borderscape is not just a question of what happens on the border or in the immediate borderlands, but also of what happens at any spatial distance from it, at any scale, on any level, in any dimension. » Les ‘borderscapes’ ne se trouvent donc pas nécessairement ou même rarement dans les « bords territoriales » ; ils ne se laissent pas non plus intégrer facilement dans des catégories nationales ou autres catégories territoriales qui sont éventuellement mobilisées. Leur localisation reste un projet empirique, qui suit les efficacités sociales d’une ou plusieurs frontières nationales « into a multiplicity of fields and locations » (Rosello et Wolfe, 2017, p. 7) et qui peut ainsi déterminer une diffusion spatiale plus ou moins extensive de la formation examinée.

(3) Frontière comme formation épisodique : Les ‘borderscapes’ sont des formations hautement vivaces (Rajaram/Grundy-Warr, 2007, p. x), mobiles (Brambilla, 2015, p. 22), ainsi que continuellement reproduites (Brambilla, 2015, p. 26) et donc transitoires (Bürkner, 2017, p. 86). Leur caractère éphémère est spécifié ici comme épisodique et ce à double titre : les « frontières comme paysage » doivent être interprétées comme épisodiques tant dans leur diffusion spatiale que dans leur temporalité, car elles sont liées aux conditions sociales, culturelles, politiques et spatiales en constante évolution. Cela suggère que les ‘borderscapes’ pourraient uniquement être « capturés » empiriquement sous forme d’instantanés ; leurs ré-formations continuelles ouvrent cependant des perspectives diachroniques, qui aident, à leur tour, à comprendre le devenir des « frontières en tant que paysages » dans l’espace et le temps. Voici comment Brambilla (2015, p. 27) argumente également en critiquant des considérations ahistoriques répandues : « [T]he borderscapes concept enables us to understand that the time-space of borders is inherently unstable and infused with movement and change. Furthermore, the focus on borderscapes avoids the ahistorical bias, which besets much of the discourse on borders and globalisation. » Les ‘borderscapes’ représentent donc des liaisons spatio-temporelles en constante évolution, à travers lesquels les frontières apparaissent et qui produisent des espaces et des temporalités multiples de manière épisodique.

(4) Frontière comme formation en perspective : En fonction de la perspective adoptée, les « frontières comme paysage » se présentent différemment et déploient différentes significations. Cela signifie que les ‘borderscapes’ sont aussi une question de mise en perspective : « The border is a ‘perspectival’ construction […] as a set of relations that have never been given, but which vary in accordance with the point of view adopted in interpreting them. » Brambilla (2015, p. 22) se réfère ici au terme « scape » d’Appadurai (1996, p. 33). Ce-dernier explique, que scapes seraient « not objectively given relations that look the same from every angle of vision but, rather, that they are deeply perspectival constructs, inflected by the historical, linguistic, and political situatedness of different sorts of actors ». Les ‘borderscapes’ sont donc situés ce qui décrit Brambilla (2015, p. 25) en utilisant l’image du kaléidoscope. Cette métaphore est censée montrer, comment les nombreuses composantes et les relations complexes de la formation peuvent être considérées, comment leurs ré-formations peuvent être conçues de manière variable dans l’espace et le temps et combien de perspectives et ainsi de points d’accès analytiques se produisent sur la « frontière comme paysage ».

Le dernier aspect en particulier rejoint l’intention de Brambilla (2015, p. 27), « to ‘humanise’ borders », car la perspective kaléidoscopique permet d’analyser les frontières, afin de « taking into account not only the ‘big stories’ of the nation-state construction, but also the ‘small stories’ that come from experiencing the border in day-to-day life […] also considering their visible and hidden interactions. » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 25) Dans ce contexte, considérer les ‘borderscapes’ comme une formation en perspective représente à la fois une approche, qui exploite les multiples constellations avec leurs multivalences respectives de la frontière (Wille, 2021, p. 112), et qui rend ainsi visibles les existences opprimées.

(5) Frontière comme formation contestée : La perspective critique sur les frontières introduite ci-dessus qui se reflète dans la considération des ‘borderscapes’ en tant que formation en perspective est accentuée par Brambilla (2021a, p. 14) par la focalisation privilégiée sur les « borders’ conflicting multiplicity ». Ainsi, elle aborde l’interaction dynamique et conflictuelle des composantes des ‘borderscapes’, qui caractérise les frontières comme des formations contestées au sens de « site[s] of struggle » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 29). L’accent mis sur l’intersection entre « hegemonic borderscapes » et « counter-hegemonic borderscapes » est dû à une double préoccupation : Il s’agit d’une part, de dévoiler les techniques de marginalisation et d’invisibilisation et d’autre part, de renforcer une conception des frontières en tant que « engine[s] of social organisation and change » (Brambilla, 2015, p. 26) :

[It] means giving visibility back to stories of people on the move, of people who live in the borderlands, of ‘people who make opportunities, not violence, at the edges of the state’ […]. It means capturing the possibility of alternative border futures, through which people can effectively change the ‘terms of recognition’ within which they are generally trapped, opening up new political spaces of subjectivation and agency that disrupt the hold that borders […] have over people’s lives and move towards alternative forms of political arrangements, beyond the contours of present political categorisations. (Brambilla, 2021a, p. 16)

Considérer les frontières comme une formation contestée ne rend donc pas uniquement visibles les existences marginalisées ou les discours invisibilisés, elle présente également les frontières comme des espaces de possibilités et ainsi comme des ressources pour des « alternative border futures » (Brambilla, 2021a, p. 16), qui s’articulent (peuvent s’articuler) dans des ordres, des subjectivisations et des empouvoirements alternatifs.

Il faut contextualiser les explications données sur des ‘borderscapes’. Les principes fondamentaux et les aspects partiels de l’approche reposent ici avant tout sur les travaux de Brambilla, qui a présenté des réflexions théoriques et conceptuelles élaborées sur la « frontière comme paysage ». Bien que celles-ci ont été et continuent d’être largement reçues dans la recherche sur les frontières, cette approche, qui conçoit les frontières comme des formations relationnelles, diffusées, épisodiques, en perspective et contestées, est en aucun cas partagée de manière identique et pratiquée de façon conséquente. Il faut plutôt observer différentes appropriations des ‘borderscapes’, qui s’inscrivent plus ou moins dans les principes fondamentaux et mettent des accents spécifiques.

4. Appropriations

Les principes fondamentaux et aspects partiels de l’approche, qui ont été présentés, doivent être considérés comme un cadre théorique et conceptuel, dans lequel agissent des chercheurs sensibles à la complexité et qui laissent la place à des appropriations spécifiques en fonction des questions ou aspects pratiques de recherche. Krichker (2019, p. 1) note dans ce contexte : « Emerging ‘borderscape’ studies deal with a variety of divergent topics with their own distinct interpretation of the concept. » Deux de ces modes d’interprétation ou d’appropriation issues des études culturelles des frontières sont présentées ci-après à titre d’exemple, dans une perspective conceptuelle.

Dans son essai Border Aesthetics and Cultural Distancing in the Norwegian-Russian Borderscape, le spécialiste en littérature Johan Schimanski (2015) examine le rôle de l’art et de la littérature dans les (de)stabilisations de frontières. À cet effet, il utilise l’approche des ‘borderscapes’ et analyse l’exemple de la frontière russo-norvégienne. Il différencie de manière conséquente le « paysage à la frontière » et la « frontière comme paysage », qui, dans son exemple, se recoupent partiellement sur le plan empirique. La conception des ‘borderscapes’ de Schimanski est fondée sur l’idée d’un réseau complexe et diffus, maintenu par des stratégies rhétoriques, symboliques et discursives (contestées), qui renforce et renverse les logiques d’ordre territorial. Les ‘borderscapes’ sont en conséquence conçus comme « an ambivalent space of […] power and resistance » (Schimanski, 2015, p. 37), qui englobe tous les éléments impliqués dans les (de)stabilisations des frontières. Pour les définir plus en détails, l’auteur explique tout d’abord les développements historiques (culturels) de la région frontalière russo-norvégienne et le rôle de sa frontière au niveau mondial et national. En outre, il thématise le « technoscape of the border » (Schimanski, 2015, p. 40), qui se manifeste localement par des panneaux, des postes de contrôle, des barrières, etc., mais aussi par les « techniques de filtrage et de tri » mondialement standardisées à la frontière, dans les consulats et les ambassades. Ensuite, il présente le « mediascape of the border » (Schimanski, 2015, p. 40), qui inclut des cartes, des guides de voyage, des histoires, des expositions, des sites web, des reportages télévisés et des articles de journaux sur la région frontalière russo-norvégienne, ainsi que des médias issus du travail scientifique de terrain sur place ou des travaux artistiques, qui thématisent le principe d’ordre territorial et/ou qui ont été créés dans la région frontalière. Schimanski définit l’ensemble de ces composantes et leurs références mutuelles comme des ‘borderscapes’, bien que la sélection des composantes thématisées ne soit pas commentée.

Compte tenu de sa problématique, l’auteur examine en détail le rôle de l’art et de la littérature dans les ‘borderscapes’ : Les travaux artistiques ne doivent pas être interprétés comme des enregistrements isolés isolées qui illustrent ou représentent la frontière ; ils sont plutôt intégrés de manière relationnelle dans des contextes culturels et sociaux de signification et sont efficaces dans des négociations de frontières ou d’ordres (Schimanski, 2015, p. 40 et suiv.). Grâce à ce moment performatif, qui est particulièrement visible dans les contestations des frontières, l’art et la littérature sont tout autant pertinents dans les ‘borderscapes’ que les infrastructures frontalières ou les discours politiques : « The concept of borderscape implies that they [aesthetic works] participate in the same field of play as […] a border fence or a border commission. » (Schimanski, 2015, p. 41) Dans la partie empirique de cet essai, Schimanski reconstruit les négociations de la frontière russo-norvégienne à l’aide de performances, d’installations, d’expositions et de romans. Il rend productive l’idée du réseau complexe et montre des références artistiques sur les événements historiques, les symboliques frontalières locales ou les acteurs pertinents, ainsi que les stratégies esthétiques pratiquées pour contester et renégocier la frontière. Le chercheur en littératures conçoit de telles stratégies comme des actes performatifs dans le sens d’un « borderscaping », qui conteste non seulement le discours hégémonique, mais qui met surtout en évidence de multiples perspectives sur ou de la frontière russo-norvégienne et leur permet ainsi une visibilité.

Chiara Brambilla (2021b) se penche également sur les questions de l’in/visibilité dans son essai In/visibilities beyond the spectacularisation: young people, subjectivity and revolutionary border imaginations in the Mediterranean borderscape. En suivant le concept de « border spectacle » (De Genova, 2012), Brambilla problématise les récits et les images de la migration aux frontières méditerranéennes qui circulent et construisent ainsi les migrants avant tout comme une menace, essentialisent leur illégalité supposée et légitimisent la violence qu’ils subissent. La spectacularisation médiatique des frontières méditerranéennes ferait appel à des techniques de simplification, qui auraient non seulement réduit la complexité du noyau frontières-migration, mais qui ont occulté la perspective des migrants. Brambilla veut contrer de telles « politics of in/visibility » (Brambilla, 2021b, p. 84) avec une image différenciée des « Mediterranean borderscapes », qui est comprise ici tout d’abord comme une construction de la spectacularisation médiatique, ou pour reprendre les termes de De Genova (2012, p. 492) : comme une formation discursive « of both languages and images, of rhetoric, text and subtext, accusation and insinuation, as well as the visual grammar that upholds and enhances iconicity. » L’image différenciée des « Mediterranean borderscapes », apparaît chez Brambilla (2021b) à travers une complexification, qui inclut, d’une part, la perspective des migrants et/ou de ceux qui « habitent » les borderscapes et ouvre d’autre part des espaces de possibilités pour des subjectivisations et des empouvoirements. L’anthropologue conçoit cette approche et les effets de re-politisation ou de dé-spectacularisation qui en découlent comme une « political and performative method » (Brambilla, 2021b, p. 85), qu’elle appelle « borderscaping ». Le ‘borderscaping’ vise à dévoiler les efficacités des frontières méditerranéennes (spectacularisées) au quotidien, à rendre ainsi les migrants visibles et à les habiliter à aménager les frontières. A cet égard, Brambilla traite le contexte d’analyse comme une formation en perspective :

I aimed to investigate how the rhetoric and policies of borders impact, conflict and exist in a dynamic relationship with everyday life, as well as how this rhetoric and policies are experienced, lived and interpreted by those who inhabit the Italian/Tunisian borderscape. This highlights the urgency of advancing a perspective that gives voice to a multiplicity of individual and group stances dealing with the Mediterranean neighbourhood as they are embedded in the realms of identities, perceptions, beliefs and emotions, whilst also examining practices and experiences of dealing with Euro/African Mediterranean interactions, both political and territorial, as well as symbolic and cultural. (Brambilla, 2021b, p. 89)

Comme mentionné dans la citation, Brambilla examine les ‘borderscapes’ italo-tunisiens, qui ne représentent pas seulement une formation relationnelle puissant d’images et de récits. Les ‘borderscapes’ sont désormais conçus comme un paysage de discours et de pratiques (im)matériels contestées, qui se réfère aux relations africano-européennes avec leurs (dis)continuités. Pour la détermination empirique, l’anthropologue travaille avec des jeunes, qui vivent à Mazara del Vallo (Italie), certains dont la famille est originaire d’Italie et d’autres dont les parents ont immigré de Tunisie (principalement de Mahdia) il y a deux ou trois générations. Grâce à une combinaison élaborée de méthodes qualitatives qui vise à entremêler le récit et la visualisation, Brambilla recueille auprès des jeunes les perceptions, les expériences, les pratiques, etc., liées à la frontière italo-tunisienne. Elle considère ces-dernières comme des points de cristallisation des « counter-hegemonic borderscapes » ou comme des résistances performatives au sujet de la spectacularisation médiatique peu complexe des « Mediterranean borderscapes » :

Young people sketch a counter-image of the Italian/Tunisian borderscape through a resistance that is enacted […] through imagining, experiencing, and performing in the Mediterranean neighbourhood.”; “[…] young people’s imaginaries and experiences challenge the tactical, pre-emptive invisibilisation that pervades hegemonic media narratives and political discourses of the spectacle. (Brambilla, 2021b, p. 94, 98)

Les appropriations de l’approche des ‘borderscapes’ présentées ci-dessus, prennent avant tout en compte les dimensions culturelles et symboliques des (de)stabilisations des frontières. Elles conçoivent une notion des ‘borderscapes’ avec, à chaque fois, une accentuation différente, mais avec des hypothèses de base partagées, et introduisent le concept de ‘borderscaping’. Schimanski et Brambilla (ainsi que d’autres chercheur.e.s sur les frontières) différencient ainsi entre l’objet de recherche « frontière en tant que paysage » et l’activité de l’« aménagement paysager ». Cependant les deux exemples d’appropriation fonctionnent avec différentes conceptions du ‘borderscaping’, comme expliqué dans ce qui suit.

5. Ambiguïtés

Comme indiqué ci-dessus, l’attrait des ‘borderscapes’ résulte d’une certaine « theoretical and methodological vagueness » (Krichker, 2019, p. 1) qui permet aux chercheur.e.s sur les frontières différentes interprétations ou appropriations. Dans ce contexte, la critique concernant l’approche comme étant « [p]erhaps too open » (van Houtum, 2021, p. 38) se reflète fondamentalement dans la question de savoir s’il s’agit ici d’un objet de recherche ou d’une méthod(ologi)e. Cette indétermination ne se manifeste non seulement dans l’utilisation diffuse des termes « borderscapes » et « borderscaping » ; ‘borderscape’ est aussi désigné de manière variable comme « concept », « approach » ou « method ». La désignation « approche » choisie dans ce texte, doit être interprétée comme inclusive et comprend ‘borderscapes’ à la fois en tant qu’objet de recherche et en tant que méthod(ologi)e.

En tant qu’objet de recherche, les ‘borderscapes’ reposent sur la systématisation expliquée ci-dessus, en tant que formation relationnelle, diffusée, épisodique, en perspective et contestée, liée aux frontières nationales. Les ‘borderscapes’ doivent, en ce sens, être conçus comme un objet analytique (continuellement (re-)déterminé, avant ou pendant qu’il est examiné avec certaines méthodes. Cependant, la question qui se pose ici est de savoir quels éléments (im)matériels constituent les ‘borderscapes’, ou en d’autres termes : Qui ou quoi (ne) fait (pas) partie des ‘borderscapes’ et (n’) est (pas) pris en compte dans l’analyse. Les quelques affirmations concernant cette question fournissent peu d’indications, bien que leur examen puisse contrebalancer une surgénéralisation potentielle (et partiellement observable) de la « frontière ». Pour éviter cette dernière, qui est également appelée « borderism » (Gerst, 2020, p. 149), il faudrait définir plus clairement ce qui qualifie des éléments (im)matériels pour devenir des composantes des ‘borderscapes’ ou pour être considérés comme tel par les chercheur.e.s sur les frontières. À cet effet, le critère « borderness » (Green, 2012) peut, par exemple, être appliqué pour demander dans quelle mesure des éléments (im)matériels sont impliqués « to the way borders are both generated by, and/or help to generate, the classification system that distinguish (or fails to distinguish) people, places and things in one way rather than another. » (Green, 2012, p. 580) Les ‘borderscapes’ considérés peuvent toutefois être questionnés pour savoir si les éléments (im)matériels qui potentiellement les constituent sont (rendus) pertinents dans l’établissement ou la (dé)stabilisation des ordres ou des catégorisations, à travers lesquelles des frontières se manifestent. Cette enquête d’ordre méthodologique, qui tente de reconstruire une certaine frontiérité et de préciser ainsi l’objet de recherche des ‘borderscapes’, correspond à l’intention de vouloir repérer des frontières dans leurs éfficacités plus ou moins évidentes et complexes dans les processus sociétaux. Dans cette approche, il faut toutefois exclure que les chercheur.e.s sur les frontières mettent prématurément des paramètres, qui éventuellement négligent des frontiérités ou attribuent des frontiérités non pertinentes à l’objet de recherche. La frontiérité en tant que caractéristique d’identification des ‘borderscapes’ doit, comme expliqué ci-dessus, bien plus être traitée comme une question empirique axée sur la pertinence de la frontière et à laquelle les habitant.e.s des ‘borderscapes’ respectivement les chercheur.e.s dans l’optique des pratiques observées ou des discours examinés doivent répondre.

En transférant les ‘borderscapes’ dans une activité, les chercheur.e.s sur les frontières poursuivent à leur tour différentes causes méthod(olog)iques. C’est pourquoi lorsqu’il est examiné plus en détail, le ‘borderscaping’ vise différents aspects de la recherche sur les frontières axée sur la complexité :

(1) Borderscaping comme méthode de la construction d’objet : Le ‘borderscaping’ doit en ce sens être d’abord compris comme un « way of thinking about the border » (Schimanski, 2015, p. 35) visant une conception complexe des frontières. Ce « way of thinking », qui sert à déterminer qui ou quoi constitue les ‘borderscapes’, à la lumière d’une question de recherche particulière, est décrit par Brambilla (2015, p. 22) comme un « multi-sited approach » : « [A] multi-sited approach not only combining different places where borderscapes could be observed and experienced [...] but also different socio-cultural, political, economic as well as legal and historical settings. » Il s’agit donc ici de suivre la frontière dans sa diffusion sociale et spatiale dans les arènes sociétales, dans lesquelles elle se produit et où elle est contestée. Cette approche, également appelée « seeing like a border » (Rumford, 2012, p. 895) dévoile les acteurs, les discours, les pratiques pertinents, etc. dans leurs liens de référence mutuels, qui permettent d’identifier les ‘borderscapes’ comme objet de recherche. Cependant, les ‘borderscapes’ ne peuvent jamais être construits comme un objet de recherche minutieusement tracé et déterminé de manière exhaustive. De fait, il s’agit toujours d’une section, qui se présente temporairement comme une constellation située, de multiples ramifications spatio-temporaires complexes de la frontière, qui se ré-forment continuellement en tant que formation intégrée dans le social.

(2) Borderscaping comme méthode de l’empirie : Cette conception du ‘borderscaping’ se concentre sur l’événement qui peut être observé de manière empirique et ainsi sur la dynamique des ou dans les ‘borderscapes’. Le ‘borderscaping’ concerne ici le processus performatif de l’ (du) (ré)aménagement (shape) de la « frontière comme paysage ». Comme avec Schimanski (2015, p. 43), l’« aménagement paysager » est ici compris comme un processus par lequel les « hegemonic borderscapes » sont contestés ou remodelés à travers des résistances. Le ‘borderscaping’ en tant que stratégie de ré-formation, reconstruite sur des données empiriques, doit donc avant tout être situé dans les moments de contestation des frontières, qui ouvrent dans le même temps des espaces de possibilités.

(3) Borderscaping comme méthode de recherche sur les frontières engagée : Cette conception permet de déployer les espaces de possibilités des frontières « [by] moving from a rendering of the border as a space of crisis to […] a space of political creativity, as a space […] [of] politics of possibilities to come. » (Brambilla, 2021a, p. 15) Le ‘borderscaping’ en tant que technique de (ré)aménagement ou même d’intervention, doit ici être situé entre la recherche en termes de production de connaissances critiques et les ‘borderscapes’ en termes de réalité de vie frontiérisée. Comme le démontre Brambilla (2021b, p. 85), il s’agit de concevoir l’activité de recherche elle-même comme une « political and performative method », qui permet dévoiler la complexité et la contestation des ‘borderscapes’ dans le but de rendre visible l’invisible et/ou de permettre aux existences opprimées d’aménager les frontières. Cette cause engagée, qui fait en même temps des chercheur.e.s sur les frontières des « paysagistes », s’inspire de l’approche « Border as Method » (Mezzadra et Neilson, 2013), qui adresse les connaissances sur le monde (frontiérisé) et son co-aménagement à parts égales. « It is above all a question of politics, about the kinds of social worlds and subjectivities produced at the border and the ways that thought and knowledge can intervene in these processes of production. To put this differently, we can say that method for us is as much about acting on the world as it is about knowing it. » (Mezzadra et Neilson, 2013, p. 17)

Les ambiguïtés de l’approche des ‘borderscapes’ ont été ici systématisées par le biais de différentiations analytiques et ont ainsi pu rendu en sujet de discussion pour le débat interdisciplinaire, qui doit déclencher des développements théoriques et conceptuels.

6. Conclusion

Cet article a mis en évidence la conception la plus répandue des ‘borderscapes’ dans la recherche sur les frontières et a exposé l’approche partiellement sous-déterminée et interprétée de manière variable dans ses principes fondamentaux. À cet effet, les ‘borderscapes’ ont été systématisés comme une formation relationnelle, diffusée, épisodique, en perspective et contestée et des applications possibles ont été présentées. L’approche situe la frontière dans nombreux processus sociétaux, qui sont modifiables et aménageables, liés les uns aux autres de manière trans-scalaire et controversée, et qui, dans leur interaction complexe, établissent ou (dé-)stabilisent des frontières. Les ‘borderscapes’ transforment donc les frontières en paysages diffus de leurs efficacités et négociations multiples, qui ont certes lieu aux « bords territoriales », mais qui en sont conceptuellement émancipées. De cette façon, l’approche offre une analyse qui échappe au « territorial trap » (Agnew, 1994), sensibilise à la complexité de la frontière et la considère comme une ressource. Car l’une des forces des ‘borderscapes’ est également de concevoir les acteurs, les pratiques, les discours, etc. efficaces dans les (dé)stabilisations des frontières comme une formation relationnelle par laquelle les expériences, les représentations, les récits, les corporalités, et plus encore, entrent dans un contexte d’observation commun et complexe. La relationnalité qui le caractérise, relie la dimension symbolique à la dimension matérielle et comble ainsi le « metaphorical-material border gap » (Brambilla, 2021b, p. 86). En outre, les liens de référence permettent de complexifier les ‘borderscapes’ à travers l’analyse (critique) et donc de brosser un portrait différencié de la frontière et d’exploiter des espaces de possibilités de la frontière.

Outre ces forces, les problèmes et les ambiguïtés de l’approche ont également été cités, qui compliquent le débat interdisciplinaire au sein des études sur les frontières. En ce qui concerne les ‘borderscapes’ comme objet de recherche, la question qui n’a pas été suffisamment clarifiée demeure, à savoir ce qui qualifie les composantes éventuellement considérées comme faisant partie de la formation puissante et, par conséquent, comme devenant l’objet de l’analyse. À cet effet, il manque des réflexions conceptuelles et surtout socio-théoriques, qui dépassent la pensée scalaire et tiennent compte de la relation entre les composantes matérielles et immatérielles ou humaines et non-humaines dans leur interaction complexe. La suggestion faite qui consiste à axer la construction des ‘borderscapes’ sur l’empirie par le biais de la pertinence de la frontière, peut faire face à ce besoin et indique en même temps le potentiel de l’approche en tant que méthod(ologi)e : « Rather than a as a concrete empirical category, the concept of borderscapes is better used as a way of approaching bordering processes […] wherever a specific border has impacts, is represented, negotiated or displaced. » (Laine, 2017, p. 13) Cette perspective, qui tente de conjuguer la question de l’objet de recherche et de la méthod(ologi)e, s’inscrit dans des conceptions identifiées du « bordercaping » en tant que méthode de construction d’objet ou de recherche engagée sur les frontières.

Outre une production de connaissances critiques, l’approche vise avant tout à prendre en compte et à comprendre de manière appropriée la complexité des frontières. Les ‘borderscapes’ sont sans aucun doute un instrument adapté : « [The] borderscapes approach […] represents a highly promising tool for ‘re-assembling’ border complexity. » (Scott, 2020b, p. 10) ; ou : « [T]he borderscape notion offers tools to enhance our understanding of complex bordering, ordering and othering processes. » (Brambilla, 2021a, p. 15) Toutefois, on observe dans la pratique de la recherche et dans le débat conceptuel sur les ‘borderscapes’, que les conclusions (obtenues) sur la complexité des frontières sont souvent insuffisantes. De nombreux travaux s’épuisent à recenser le plus grand nombre possible de composantes des ‘borderscapes’ pour les examiner ensuite de manière plus ou moins isolée les unes des autres. Les nombreux liens de référence, qui représentent non seulement l’interaction des composantes des ‘borderscapes’, mais qui font alors de la frontière un objet complexe, sont souvent négligés. En effet, les effets émergents de l’établissement ou de la (dé)stabilisation des frontières qui émanent des ‘borderscapes’, ne sont pas dus aux composantes de la formation relationnelle, mais à leur interaction complexe, qui a un effet performatif. Le philosophe et chercheur en complexité, Paul Cillier (2016, p. 142), met en évidence cette caractéristique centrale des ‘borderscapes’, lorsqu’il explique des systèmes complexes : « Complex systems display behavior that results from the interaction between components and not from characteristics inherent to the components themselves. This is sometimes called emergence. » Cette conception de la complexité sur laquelle repose l’approche des bordertextures (Wille, Fellner, Nossem, à paraître) se concentre sur les liens de référence mutuels qui nous permettent de formuler les questions sur le fonctionnement des ‘borderscapes’ et donc sur les logiques performatives de la (dé)stabilisation des frontières. Dans ce contexte, l’attention est enfin attirée sur la confusion entre la complexité et la multiplicité que l’on rencontre fréquemment dans la recherche sur les ‘borderscapes’ (et au-delà). La multiplicité de la frontière, avec laquelle un grand nombre d’acteurs, de pratiques et de discours pertinents dans les ‘borderscapes’ (ou par ailleurs la multiplicité des dimensions de la frontière) est en règle générale thématisée, ne permet pas (encore) de déterminer ou même de comprendre la complexité de la frontière. Il faut plutôt se tourner vers les processus entre les acteurs, les pratiques, les discours (ou les dimensions) pertinents, qui deviennent efficaces dans leur interaction en tant que (dé)stabilisations de frontières et peuvent être cernés par le biais leurs liens référentiels mutuels.

Références

Agnew, J. (1994) ‘The Territorial Trap: The Geographical Assumptions of International Relations Theory’, Review of International Political Economy, vol. 1 n° 1, pp. 53-80.

Dell’Agnese, E. (2005) ‘Bollywood’s Borderscapes’, Paper presented at AAG Pre-Conference at the University of Colorado, Boulder, 3-5 avril.

Dell’Agnese, E. et Amilhat-Szary, A. L. (2015) ‘Introduction: Borderscapes: From Border Landscapes to Border Aesthetics’, Geopolitics, vol. 20 n° 1, pp. 4-13, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2015.1014284.

Appadurai, A. (1996) Modernity at Large. Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, Minn.

Brambilla, C. (2015) ‘Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscapes Concept’, Geopolitics, vol. 20 n° 1, pp. 14-34, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.884561.

Brambilla, C. (2021a) ‘Revisiting ‘bordering, ordering and othering’: an invitation to ‘migrate’ towards a politics of hope’, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, vol. 112 n° 1, pp. 11-17, https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12424.

Brambilla, C. (2021b) ‘In/visibilities beyond the spectacularisation: young people, subjectivity and revolutionary border imaginations in the Mediterranean borderscape’, dans Schimanski, J. et Nyman, J. (Éds.), Border images, border narratives: The political aesthetics of boundaries and crossings, Manchester University Press, Manchester, pp. 83-104.

Brambilla, C. et Jones, R. (2019) ‘Rethinking borders, violence, and conflict: From sovereign power to borderscapes as sites of struggles’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819856352.

Brambilla, C. et al. (Éds.), (2015) Borderscaping: Imaginations and Practices of Border Making, Ashgate, Farnham.

Bürkner, H.-J. (2017) ‘Bordering, Borderscapes, Imaginaries: From Constructivist to Post-Structural Perspectives’, dans Opilowska, E. et al. (Éds.), Advances in European Borderlands Studies, Nomos, Baden-Baden, pp. 85-107.

Cilliers, P. (2016) ‘Complexity, deconstruction and relativism’, dans Cilliers, P., Critical Complexity. Collected Essays (éd. par Rika Preiser), DeGruyter, Berlin/Boston, pp. 139-152.

Cooper, A. (2020) ‘How do we theorise borders, and why should we do it? Some theoretical and methodological challenges’, dans Cooper, A. et Tinning, S. (Éds.), Debating and Defining Borders. Philosophical and Theoretical Perspectives, Routledge, London, pp. 17-30.

Dolff-Bonekämper, G. et Kuipers, M. (2004) ‘Boundaries in the Landscape and in the City’, dans Dolff-Bonekämper, G. (Éd.), Dividing Lines, Connecting Lines – Europe’s Cross-Border Heritage, Council of Europe, Strasbourg, pp. 53-72.

Euborderscapes (2016) ‘EUBORDERSCAPES – Bordering, Political Landscapes and Social Arenas: Potentials and Challenges of Evolving Border Concepts in a post-Cold War World‘, Large-Scale Integrating Project FP7-SSH-2011-1-290775, Final Report WP1.

De Genova, N. (2012) ‘Border, Scene and Obscene’, dans Wilson, T. M. et Donnan, H. (Éds.), A Companion to Border Studies, Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, pp. 492-504.

Gerst, D. (2020) ‘Epistemic border struggles: exposing, legitimizing, and diversifying border knowledge at a security conference‘, dans Wille, C. et Nienaber, B. (Éds.), Border Experiences in Europe. Everyday Life – Working Life – Communication – Languages, Nomos, Baden-Baden, pp. 143-166, https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845295671-143.

Green, S. (2012) ‘A Sense of Border’, dans Wilson, T. M. et Donnan, H. (Éds.), A Companion to Border Studies, Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, pp. 573-592.

Harbers, A. (2003) ‘Borderscapes, The Influence of National Borders on European Spatial Planning’, dans Brousi, R., Jannink, P., Veldhuis, W. et Nio, I. (Éds.), Euroscapes, Must Publishers/Architectura et Amicitia, Amsterdam, pp. 143-166.

Van Houtum, H. (2021) ‘Beyond ‘Borderism’: Overcoming Discriminative B/Ordering and Othering’, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, vol. 112 n° 1, pp. 34-43, https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12473.

Van Houtum, H. et Van Naerssen, T. (2002) ‘Bordering, ordering and othering’, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, vol. 93 n° 2, pp. 125-136.

Krichker, D. (2019) ‘Making Sense of Borderscapes: Space, Imagination and Experience, Geopolitics’, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2019.1683542 (online first).

Kun, J. (2000) ‘The Aural border’, Theatre Journal, vol. 52 n° 1, pp. 1-21.

Laine, J. (2017) ‘Understanding borders under contemporary globalization’, Annales Scientia Politica, vol. 6 n° 2, pp. 5-18.

Mezzadra, S. et Neilson, B. (2013) Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor, Duke University Press, Durham.

Minghi, J. et Rumley, D. (Éds.), (1991) The Geography of Border Landscapes, Routledge, London/New York.

Nyman, J. et Schimanski, J. (2021) ‘Introduction: images and narratives on the border’, dans Schimanski, J. et Nyman, J. (Éds.), Border images, border narratives: The political aesthetics of boundaries and crossings, Manchester University Press, Manchester, pp. 1-20.

Parker, N. et Vaughan-Williams, N. (2012) ‘Critical Border Studies: Broadening and Deepening the ‘Lines in the Sand’ Agenda’, Geopolitics, vol. 17 n° 4, pp. 727-733, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2012.706111.

Parker, N. et al. (2009) ‘Lines in the Sand? Towards an Agenda for Critical Border Studies ’, Geopolitics, vol. 14 n° 3, pp. 582-587.

Rajaram, P. K. et Grundy-Warr, C. (Éds.), (2007) Borderscapes. Hidden Geographies and Politics at Territory’s Edge, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis/London.

Rosello, M. et Wolfe, S. F. (2017) ‘Introduction’, dans Schimanski, J. et Wolfe, S. F. (Éds.), Border Aesthetics: Concepts and Intersections, Berghahn, New York/Oxford, pp. 1-24.

Rumford, C. (2012) ‘Towards a Multiperspectival Study of Borders’, Geopolitics, vol. 17 n° 4, pp. 887-902, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2012.660584.

Schimanski, J. (2015) ‘Border Aesthetics and Cultural Distancing in the Norwegian-Russian Borderscape’, Geopolitics, vol. 20 n° 1, pp. 35-55, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.884562.

Scott, J. (2017) ‘Globalisation and the Study of Borders’, dans Scott, J. (Éd.), Cross-Border Review. Yearbook 2017, CESCI, Budapest, pp. 5-28.

Scott, J. W. (2020a) ‘Borderscapes’, dans Wassenberg, B. et Reitel, B. (Éds.), Critical dictionary on borders, cross-border cooperation and european integration, Peter Lang, Bruxelles, pp. 151-152.

Scott, J. W. (2020b) ‘Introduction to “A Research Agenda for Border Studies”’, dans Scott, J. W. (Éd.), A Research Agenda for Border Studies, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp. 3-24.

Stojanovic, D. (2018) ‘Post-modern Metamorphosis of Limological Discourses: From “Natural” Borders to Borderscapes’, Nagoya University Journal of Law and Politics, vol. 276, pp. 97-161.

Strüver, A. (2005) Stories of the ‘Boring Border’: The Dutch-German Borderscape in People’s Minds, LIT-Verlag, Münster.

Wille, C. (2021) ‘Vom processual shift zum complexity shift: aktuelle analytische Trends der Grenzforschung’, dans Gerst, D. et al. (Éds.), Grenzforschung. Handbuch für Wissenschaft und Studium, Nomos, Baden-Baden, pp. 106-120, https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845295305-106.

Wille, C. et al. (Éds.), (i.E.) Bordertextures. A Complexity Approach to Cultural Border Studies, transcript, Bielefeld.

Borderscapes

1. Introduction

‘Borderscapes’ as an approach that includes conceptual and methodological aspects represents the further development of the “‘bordering turn’” (Cooper, 2020, p. 17), which took place in the course of the renaissance of borders and the resulting research impulses in the 2010s. Despite an ambiguous definition and a certain conceptual openness, ‘borderscapes’ is widespread in both geopolitical and cultural border studies in such a way that the impression could arise that “speaking about borderscapes is almost a fashion” (dell’Agnese and Amilhat-Szary, 2015, p. 5). This in itself indicates that the approach is widely received. Critical discussions or considerations about its operationalization, however, remain the exception. In addition to this criticism, however, several of the approach’s strengths should be emphasized, as they have largely enforced a differentiated conception of borders in border studies. The understanding of borders in ‘borderscapes’ – which will be stated in advance for didactic reasons – will join the ranks of the “complexity shift” (Wille, 2021) as a young trend in Border Studies. This includes the concerns of Border Studies researchers that borders are no longer to be seen ‘only’ as effects of ‘straightforward’ bordering processes (van Houtum and van Naerssen, 2002) or as unquestioned “lines in the sand” (Parker et al. 2009) but also to examine borders as powerful ensembles of multiple actors, social arenas, (im)materialities, multi-localities, multivalences, or temporalities. This more complex view sees the border as a powerful formation (and one not existing outside of such a formation) and is interested in how it works, as well as implying the ‘borderscapes’ approach. It understands borders as transscalar formations of elements. The complex interplay of these elements creates borders: “The borderscape is not purely an external effect of the border, but an assemblage in which bordering takes place” (Schimanski, 2015, p. 40).

The idea of formation, which, here, represents the border, is expressed in the numerous paraphrases which attempt to explain ‘borderscapes’: “panoramas,” “contexts” (Scott, 2020a, p. 151), “zone” (Rajaram and Grundy-Warr, 2007, p. xxx), “spaces” (Brambilla, 2015, p. 18), “fluid field” (Brambilla, 2015, p. 26), “sites of struggle” (Brambilla and Jones, 2019) and “horizon” (Stojanovic, 2018, p. 147). The descriptions range from static to dynamic understandings, but also from abstract to concrete and largely spatial views. The interpretation spectrum refers to the various interpretations of the approach in border studies, which is itself an “interdisciplinary borderland” (Cooper, 2020, p. 18). This article makes its way into this very borderland to reconstruct the basics of the approach in light of its “‘irresistible vagueness’” (Krichker, 2019, p. 2) and “polysemicity” (Brambilla, 2015, p. 20). To do so, the uses of ‘borderscapes’ starting at the turn of the millennium and the understandings of the term implied with them are examined first. The particularly widespread understanding is represented with “border as a landscape” and linked with ‘borderscapes’ as an approach of complexity-oriented border studies. To this end, ‘borderscapes’ will be systematized primarily based on the work of the anthropologist Chiara Brambilla as a relational, diffused, episodic, perspectival, and contested formation that is related to one or more national borders. Finally, possible appropriations of the approach will be presented using examples of Cultural Border Studies and the conceptual openness of ‘borderscapes’, which is particularly reflected in method(olog)ical ambiguities, will be discussed.

2. Term Use

The term ‘borderscapes’ was coined by the artists Guillermo Gómez-Peña and Roberto Sifuentes when they performed their artistic piece Borderscape 2000: Kitsch, Violence, and Shamanism at the End of the Century (1999) (dell’Agnese and Amilhat Szary, 2005, pp. 4f.). After the turn of the millennium, the term could also be found in academia, even if only sporadically at first: in the essay Borderscapes, the Influence of National Borders on European Spatial Planning by Arjan Harbers (2003), in the chapter Boundaries in the Landscape and in the City by Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper and Marieke Kuipers (2004), in the lecture Bollywood’s Borderscapes by Elena dell’Agnese (2005) at a conference of the American Association of Geographers, and in the book Stories of the ‘Boring Border’: The Dutch-German Borderscape in People’s Minds by Anke Strüver (2005).

After the mid-2000s, ‘borderscapes’ became increasingly used in academic debate. Decisive factors here were the publication of the book Borderscapes: Hidden Geographies and Politics at Territory’s Edge by the social anthropologist Prem Kumar Rajaram and the geographer Carl Grundy-Warr (2007) as well as a series of conferences within the framework of the International Geographical Union: Borderscapes: Spaces in Conflicts/Symbolic Places/Networks of Peace (Trento, 2006), Borderscapes II: Another Brick in the Wall? (Trapani, 2009) and Borderscapes III (Trieste, 2012). The term became popular in the 2010s, presumably due to the research project EUBORDERSCAPES – Bordering, Political Landscapes and Social Arenas: Potentials and Challenges of Evolving Border Concepts in a post-Cold War World (Euborderscapes, 2016). The multidisciplinary project (2012-2016) with 22 partners from 17 countries, funded by the 7th European Research Framework Program, has led to numerous intellectual impulses and scientific publications which have profiled the term as an approach of complexity-oriented Border Studies. These include, among others, the anthology Borderscaping: Imaginations and Practices of Border Making (Brambilla et al., 2015).

The short overview of the composition of the word consisting of ‘border’ and ‘landscapes’ mirrors the word’s predominantly plural use, its comparatively new popularity, and its use in various fields of research. This is also linked to different understandings of the term that have emerged in more or less theoretical and conceptual reflections in current Border Studies (in the following also dell’Agnese and Amilhat Szary, 2005):

(1) Landscape at the border: The article by Harbers (2003) serves as an example for the understanding of ‘borderscapes’ as a landscape at the border. He understands ‘borderscapes’ as a landscape that is characterized or influenced by the presence of a national border: “[W]e shall describe the distortions borders bring to the built environment or nature as ‘border solidifications’, or borderscapes.” (Harbers, 2003, p. 143) Accordingly, ‘borderscapes’ stands for a physical space on or along a national border in which the discontinuities of state sovereignty materialize. This understanding also reflects some articles from political geography, which, in the first half of the 20th century, already addressed the role of the state as a “landscaper”.

(2) Landscape through the border: This understanding of ‘borderscapes’ is also about the shaping of physical space in connection with national borders. However, the authors Dolff-Bonekämper and Kuipers (2004) do not ask to what extent the discontinuities of state sovereignty materialize in a landscape at the border, but rather what role the border plays in the process of creating a landscape. Thus, together with Julian Minghi and Dennis Rumley (1991), they cite the spatial development in border regions and the discontinuities that are effective in this process: competencies, political styles, decision-making processes, etc. The authors thus understand ‘borderscapes’ as a cross-border landscape that arises through the border – that is, through the productive negotiations of the discontinuities implied by the state border.

(3) The border as a landscape: This understanding sees the border itself as a continually changing landscape and – like the performance artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña (Kun, 2000) – is based on Scapes of Globalization by Arjun Appadurai (1996). In the course of the globalization debate of the 1990s, the anthropologist used this concept to describe the world as a transnational formation of flows, exchange processes and overlaps, which, contrary to the notion of a static-binary organized world, represents a hybrid and unstable global landscape. The concept of landscape is used here metaphorically to describe dynamic, transscalar interdependencies that can be mapped spatially, but not in the mosaic of national order. ‘Borderscapes’ in this sense emancipates itself from space on or along the “territorial margins” and stands itself for a mobile and relational space:

In line with Appadurai’s reflection, the borderscapes concept brings the vitality of borders to our attention, revealing that the border is by no means a static line, but a mobile and relational space. […] Thus, the concept of borderscape enables a productive understanding of the processual, de-territorialised and dispersed nature of borders and their ensuing regimes and ensembles of practices. (Brambilla, 2015, p. 22)

The understandings of the ‘borderscapes’ term presented refer consistently to a landscape, but with different areas of focus. In the first two understandings of the term, a physical-territorial space is in the foreground as a landscape, whose geographical location on, along, or across a state border is central and which is designed in different ways by an external agent. In the third understanding of the term, the idea of a territorial landscape is replaced by that of an interwoven context, the design of which does not come from any external agent and geographical localization is of secondary importance. The landscape, understood here as multi-local, stands for the border, to which, as a dynamic formation, a certain creative power is ascribed. Correspondingly, the performative meaning of landscape, which aims at a socio-cultural reshaping or shaping, undergoes a specific and sometimes critical accentuation in the understanding of “border as a landscape”: “the notion of ‘scapes’ is part of a political project of ‘making’ that highlights the ways in which the ‘borderscape’ affords particular sets of reproductive practices and shapes political subjectivities in a particular manner.” (Brambilla, 2015, p. 24) ‘Borderscapes’ in the sense of “border as a landscape” thus differs in several respects from the preceding understandings of the term. At the same time, “border as a landscape” is considered to be the most widespread understanding of ‘borderscapes’ in current Border Studies (Krichker, 2019, p. 4), which is why it will be examined in more depth in this article.

3. Border as a Landscape

The popularity of the ‘borderscapes’ approach is undoubtedly due to the research project with almost the same name mentioned above. One of the Border Studies researchers involved made a significant contribution to the fact that ‘borderscapes’ developed from an emerging term to a widely received approach in complexity-oriented border studies: Chiara Brambilla’s article Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscape Concept (2015). Although it does not offer an ultimate definition or operationalization of the approach, it does provide a multitude of theoretical perspectives and conceptual considerations on how borders can be thought of in a complex and critical manner and finally examined. In the article, the anthropologist aimed to present “a novel ontological outlook […] or the contemporary situation of globalisation and transnational flows where borders appear, disappear, and reappear with the same but different locations, forms and functions.” (Brambilla, 2015, p. 26). To do so, she drew connections to the then-still-young critical border studies (Parker et al. 2009; Parker and Vaughan-Williams 2012) and attempted to use alternative approaches, which overcome the Western model of thinking of fixed binaries and open up borders as constructions that are unstable in space and time, in order to focus on topics and aspects which border studies had hardly touched on up until that point in time. Brambilla proposed a “processual ontology” (Brambilla, 2015, p. 26) for borders that recognizes, “that reality is evolving and constantly emerges and reemerges showing that being and becoming are not inseparable.” (Brambilla, 2015, p. 26)

From this perspective, which emphasizes the socially-made nature and the changeability of borders, bordering practices are seen as continuously reproduced and dynamic performances that are embedded in social processes or articulate themselves through them. The focus on the social arenas of borders owes itself to the concern “to ‘humanize’ borders” (Brambilla, 2015, p. 27), with which Brambilla aims to bring the collective representations, individual experiences, and effects of borders into view, and make them analyzable: “[...] focusing on how borders are embedded in the practice of the ordinary life and continuously emergent through the performative making and remaking of difference in everyday life.” (Brambilla, 2021a, p. 15). In addition, a critical perspective on borders should be taken, which focuses on the negotiation of ethically or legally legitimized bordering practices, which are part of everyday life, as well as bordering practices which result from resistance or subversion (Brambilla, 2015, p. 20). Brambilla understands such negotiation processes in the field of tension between so-called “hegemonic borderscapes” and “counter-hegemonic borderscapes” not simply as social arenas in which borders are articulated in a particularly explicit way. At these “sites of struggle” (Brambilla, 2015, p. 29) suppressed existences and alternative discourses emerge, which the approach aims to make visible. In this context, Brambilla (2021a, p. 14) sees ‘borderscapes’ “as shifting fields of claims, counter-claims and negotiations among various actors and historically contingent interests and processes.”

These explanations serve to present the main features of ‘borderscapes’. However, the conception of “border as a landscape” raises further questions, such as the constituents of ‘borderscapes’, their connections, spatial-territorial references and much more. These and other partial aspects of the approach are discussed below.